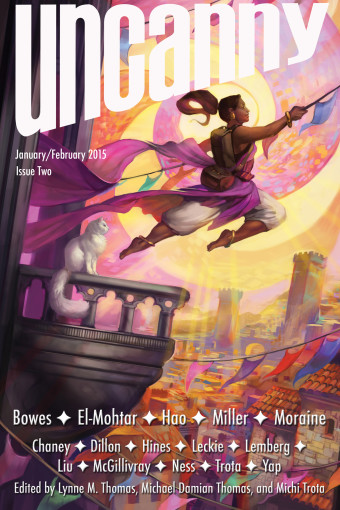

Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a space for conversation about recent and not-so-recent short stories. For this installment, I wanted to take a look at the second issue of Lynne and Michael Thomas’s newest project, Uncanny Magazine, since I found the first intriguing and enjoyable. I was particularly interested in the story-in-translation that headlines the issue’s fiction selection, “Folding Beijing,” written by Hao Jingfang and translated by Ken Liu.

The January/February issue of Uncanny also contains original work from Sam J. Miller, Amal El-Mohtar, Richard Bowes, and Sunny Moraine; a reprint from Anne Leckie; nonfiction including an essay from Jim C. Hines; and finally a handful of poems and interview. (It’s a little bit of a shame the remit of this column series is just the fiction, sometimes—there’s some other very good stuff here too.)

Firstly, I’d note that I’ve been making an effort recently to spend more time and attention here on longer works and works written by folks who I’m not familiar with—particularly if those are stories in translation. So, “Folding Beijing” was right up the alley of ‘things I’m currently looking for.’

To steal a little from her bio: Hao Jingfang has been awarded First Prize in the New Concept Writing Competition and her fiction has appeared in various publications, including Mengya, Science Fiction World, and ZUI Found. She’s also published both fiction and nonfiction books, and in the past has had work in English translation appear in Lightspeed. And, having read this piece, she’s someone whose work I’d love to see more of.

“Folding Beijing” is a handsome, thorough, and measured sort of story. It’s also long—I would guess a novelette—but lushly unfolds into that space in a manner that seems entirely necessary and appropriate. The rhetorical construction of the improbable-though-convincing technology of the folding, collapsible city is fascinating; more so is the collapsing of time, economics, and access that it enables and represents. There’s a quietly provocative undercurrent, here, a sharp though delicate criticism of the nature of global capitalism, exploitation, and hegemonic power.

And it’s not just that this is a smart story doing crunchy, smart things in a clever fashion—that’s just one layer of the thing. It’s also an emotionally resonant and intimately personal piece, grounded thoroughly through the life experience of the protagonist Lao Dao. His interactions with people in Second and First Space all revolve around issues of devotion, attraction, and survival in interesting and variable degrees. The official who helps him in First Space does so due to family ties, and it’s never implied as a sort of blackmail, but it is: Lao Dao is spared and given assistance to be a messenger for yet another person who has the power and influence to compel it of him, though it’s never spoken aloud in such a way.

That’s the delicacy that makes this piece a stand-out, too: the sense that the relations and struggles here are under the surface, pervasive and constant and real. This is not a hyperbolic dystopia, but a well-realized and concrete world where things are a certain way and people must survive it as well as possible with the tools available to them. The woman who he must deliver the love note to has a life so drastically different from the one her Second Space paramour imagines for her that it seems impossible for the two to ever meet in the middle—and, as Lao Dao knows, they won’t. She isn’t an intern as the lover assumed; she’s a married woman who works for fun and still makes more in a week than Lao Dao might be able to earn in an entire year. Compared to that graduate student lover, as well, she’s from a different world; the striations of the society make mobility almost unthinkable, though it is technically possible.

That’s one of the ways in which the radical differences of life between the spheres are not overstated, but rather come to us as broad strokes of the things Lao Dao is trying to appreciate for what they are rather than become upset about. That seems to come to fruition as well in the closing scene, where he donates what would be a huge chunk of his salary to his fellow apartment-inhabitants to quell a fight with the woman who collects rent: it is people who matter and people who keep the system ticking, for good or ill. There are only grey areas, and attempting to make something out of the life a person has to work with. He wouldn’t have been doing any of it but for having adopted an abandoned child before the story ever begins, a child who he wants to try and send to a good school.

A closing note, as well: the translation here, from Ken Liu, is impeccable and nuanced. I feel that, having read this, I have a good sense of the cadence and habits of the writer’s original language prose—it’s got a great balance and rhythm. It flowed well and read comfortably, as well-done as the story itself.

So, overall, “Folding Beijing” is a damn good story, and I appreciated its quiet strength and thorough development of its characters. Hao Jingfang is certainly a writer whose work I’d like to keep an eye out for. This story is a solid opener for a good issue of a new magazine that continues to be promising and worth checking out. Good stuff.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.